The Machine In Our Image

by Arnold Aladhami

“This seems to lie in the fact that the operation of magic is singularly literal-minded, and that if it grants you anything at all it grants what you ask for, not what you should have asked for or what you intend.” (Norbert Wiener, God and Golem Inc., 1964)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

︎︎︎

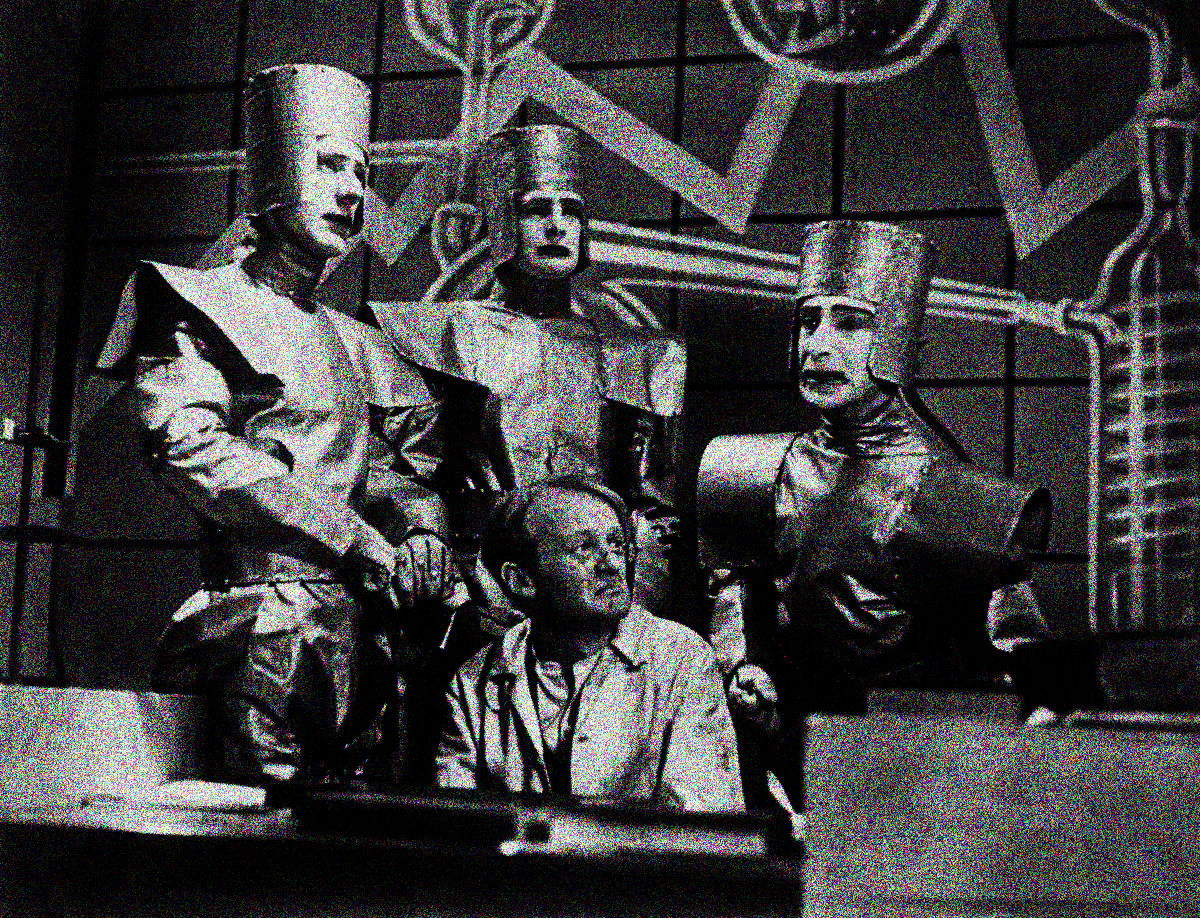

AI is among the most contested issues in technology today. The literature, both scholarly and otherwise expresses this. Issues of automata and creation of intelligent life have been discussed in philosophy and science for centuries. Fictional tales of technology and abnormal creations such as R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots) in which humans share the earth with machines are not so new. However, in many modern stories, technology is often viewed through a dystopian lens. In R.U.R., pseudo-human super-intelligent robots eventually oppose their position as slaves and labourers to their human masters and wage war on their very creators, whom they began to view as inferior.

Why are we distrustful of AI? In spite of the positive role artificial intelligence could have in various fields, why are we so transfixed on the probabilistic dangers of a ‘singularity,’ or the advent of killer robots? Could it be that these machines we imagine are, in some way, reflections of us, our values, identities, and histories, and in creating them, we recreate ourselves, both good and bad. However, moral panic often follows such apprehension and could make us skeptical and untrustworthy of our connection to machines; we could run the risk of seeing them as only threats rather than companions and assistants. Likewise, our persistence on utopia via AI could bring with it ethical concerns that we had not intended. This paper will support the idea that dystopian skepticism and utopian hope of AI comes from modern stories like R.U.R. and inherent moral values of culture, and that these will affect our perceptions, ascriptions, and realized technological outcomes in super-intelligent machines.

R.U.R. portrays many significant themes that have become commonplace in discussions surrounding AI, including hopes and fears, machine ethics, value systems, corporatism, religion, and human hubris. Much of our fear or hope comes from our literature and popularization of AI in science fiction and otherwise. The problem with narratives involving super-intelligent machines is that the technology is unrealistic; such characteristics as agency and consciousness seem plausible, almost actual, in the world of science-fiction, but in reality, AI and its capabilities are not precisely so superficial or profound. However, to say that science fiction has no place in creating real science is not to analyze such inspiration's power. Science fiction often becomes entwined in science. Terms and concepts like 'singularity' came from computer scientist and science fiction writer Victor Vinge (Chalmers, 2010) and 'robot' from R.U.R. became the very name of that science (Cave and Dihlal, 2018).

The particular time of R.U.R.’s writing was a moment of stark importance in world history, a time of revolution or warfare (Cave and Dihlal, 2018). In the story is Harry Morin, a wide-eyed, impassioned inventor, whose motive for creating his robots is to free humanity from toiling "(its) whole life away for a crust of bread...I didn't want people to be stupefied working for the boss's machine!" (Capek, 1920). Thus it so no surprise why Capek used the term 'robot,' the first instance of the word to denote machines. 'Robot' is derived from the Czech' robota' meaning 'forced labour,' or 'slave,' and in other Slavic languages, including Polish and Russian, 'robota' has a similar meaning. With its first use to denote bio-mechanical subordinates, Capek's choosing of this term was not arbitrary, a sign of the times post-Russian Revolution.

'Robotics' is now an entire field of its own, and many young engineers perhaps do not understand the irony that the origin of the term 'robot' is about a story in which the slave/labourer machines kill the humans.

‘Robot’ is thus the product of a subservient depiction of machines, a depiction which warned us of ascribing such characteristics and having incorrect perceptions. Harry Domin wished to save humanity by replacing human workers with ‘almost-human’ mechanisms. The replacement hope is often one of the significant discussions in AI alongside the dystopian fear of obsolescence (Cave & Dihlal, 2019). This concept of robots replacing us in our most laborious routines expresses that "the dream of robotics is, first, that intelligent machines can do our work for us, allowing us lives of leisure, restoring us to Eden” (Cave & Dihlal, 2019). Utopias like these often only work in theory, however.

There is the implication that a 'singularity' could bring alongside many superhuman abilities, including a strong moral agency. If humans create conscious entities with super-intelligence, this may lend itself to self-fulfilling prophecy. The value systems we encode them with may become contested, and they could begin to perceive their human creators as not only intellectually defunct but morally as well. Given that humans have enslaved populations for centuries, are we to assume that super-intelligent or conscious machines will not view their role in bettering our lives as practices of enslavement?

In his quest to save humanity, Harry Domin enslaves another population and creates an even more significant issue, not considering his machines' ethical value. Enslavement was endemic to the human condition; for thousands of years, humans had enslaved each other, forcing those enchained into horrendous circumstances of back-breaking labour and inhumanity. Despite this, our value systems coincided with slavery as a symptom of human experience and a regular occurrence. In R.U.R. is an interesting predicament that bears a resemblance to this dark history. In creating conscious machines for such purposes, we open up the issue of caring for these machines and acknowledging their agency as worthy of rights and liberties. Some philosophers believe that much moral agency and research into developing consciousness should be banned altogether (Chalmers, 2010). Currently, AI may not be as much a threat as depicted in films like 'The Terminator' or 'The Matrix.' That does not mean that as the capacity of AI grows in power and depth, public policy will not begin to push back against it.

There is also the consideration of how these stories elicit feelings of praise or resentment towards machines via different cultural systems. Many experts, believe that our apprehension towards machines originates from our spiritual histories (Schodt, 1988). In the West our fear of limiting creation is connected to such powers reserved for Gods and not flawed creatures like human beings. Jewish mysticism based on the Kabala is an ideal example of this, particularly the Golem story, a humanoid made of clay by the Rabbi of Prague, which is essentially itself the antecedent to Mary Shelley's 'Frankenstein' (Giuliano, 2020). This connection of religion and technology is, in fact, more pervasive and interwoven than we are led to believe. In 'Echoes of myth and magic in the language of Artificial Intelligence, ' Giuliano quotes historian David F. Noble, who reveals the mystical connection to AI and its advocacy of immortality, cyberspace, resurrection, the return of the one real saviour, and the apocalypse (Giuliano, 2020).

Compare this with Japan’s connection to robotics. In The Japanese have a more trusting culture surrounding robots and many believe that this originates from principles of Buddhism and Shinto, but also comes from amalgam of other faiths as well (Shodt 1988). The concept of ‘Animism’ is particularly significant, the belief that everything has an essence, or ‘soul’ even non-living things. Rocks and other such items can be revered for their ‘kami,’ or spirit, and that swords and other tools had soul. In the film “Sword Of Doom,” Toshiro Mifune famously utters this idea,’the sword is the soul, study the soul to know the sword. Evil mind, evil sword.” In some factories the introductions of robots were welcomed through consecrations where they are blessed by priests and introduced with applause. In the 1970s and 80s during Japan’s postwar economic boom, many foreigners visiting factories were surprised to see the Japanese naming their automatic machines, often ascribing names of famous actors, signers, and even taping drawings or photographs. Schodt argues that these may have been due to the newness of the machines and that such practices waned in popularity. Despite this there there is not as much skepticism of machines as there is in the west.

Japan’s connection to Shinto is only one aspect of its industriousness and openness to AI. Social and historical issues are just as significant. In the West much of the worry of machines derives from the history of the industrial revolution where lower classes were either used to labour with such machines, or suffered from rabid unemployment (Schodt, 1988). In Japan the industrial revolution had not ravaged its population and when introduced the technology was by then fully developed, was welcomed as modernizing and assisting.

Western feelings are still not as welcoming, such resentment still apparent in skepticism of machines today. Issues of dystopia are already discussed in what has become somewhat of a precursor to our relationship with AI: social media. The irony of our resentment of machines is our modern connection sentiments of the industrial revolution. Social media has produced many difficulties beside its use a platform for social connection, such as epidemics of depression, suicide, misinformation, censorship, and political and societal distrust. Its business model sells and harbours data of users, developing AI algorithms that automate methods for enhancing experience, engagement and ultimately addiction. As a result growing sentiments of AI as it is distributed in social media networks through companies like Google and other enterprises in Silicon Valley have began discussions of issues surrounding privacy and protection of use data. Policies to protect users and their data, as well as mitigating algorithmic bias are challenging the use of AI in exploiting or helping to exploit for corporate interest. Growing fear against big tech’s motives behind these platforms relate to fears that runaway advances in technology might lead to creatures or scenarios that supersede or control humanity itself (Cave & Dihlal, 2018).

Japan is the world’s largest robotics manufacturer. The trust of robots is displayed in their economy, compared with Silicon Valley whose business methods are certainly ingrained, but is more behind the scenes. Such negative perceptions affect interest in AI research or stifle AI progress for utopian outcomes like healthcare, space exploration, and climate change in favour of more militaristic capacities via an AI cold war. Too much dystopian apprehension could see policies in place that deny proper experimentation or overall interest from the general public. If this were to be the case, the number of young scientists, mathematicians, designers, and philosophers involved in AI could dwindle, transitioning to other disciplines or working in other nations more eager to analyze and conduct AI and machine research . Scientists and those in paths of discovery do not always consider the overarching consequences of their findings as these could inhibit proper fearlessness of discovery, ascension to new worlds of transcendental evolution, new phases of human life, and our planet as a whole. As Wiener writes in God and Golem Inc., "the study of their making (automata) and their theory is a legitimate phase of human curiosity, and human intelligence is stultified when man sets fixed bounds to his curiosity" (Wiener, 1960).

It is often said that “God made man in His image.” Stories and the history of automata is rife with tales of mad scientists, modern sorcerers, Gods and spirits. It is also often tied to socio-economic events that shaped human culture. The very tales and stories from which these values originate play a significant role in establishing our perceptions of machines past, present and future. Artificial intelligence brings an unknown variable that humans have not yet come to face to such degree: their own reflection. Whether humans are aware of the reality or not, we include in AI our hopes and fears, plans and desires, beliefs and suspicions. Through these values various designs, policies, and regulations are developed, as well as more personal connections to machines. Such revelations expose deep implications for the future of machine ethics, proper value loading, and moral programming in machines (Bostrom, 2017). Hence, will we be able to see beyond our desires and worries and think about AI reasonably? One thing is sure: the beginning of their development will come through us. Machines are increasingly being made in our image, and we must make sure that the images we install are of our finest.

Citations _

Bostrom, N. (2017). Superintelligence: Paths, dangers, strategies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Capek, K., Porter, C., & Majer, P. (1999). R.U.R. In Four Plays (pp.2–92). London: Methuen Drama. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781408190982.40000006

Cave, S., Nyrup, R., Vold, K., and Weller, A. (March 2019). "Motivations and Risks of Machine Ethics. Proceedings of the IEEE, 107(3), 562-574. DOI: 10.1109/JPROC.2018.2865996.

Cave, S., & Dihal, K. (2018). Ancient dreams of intelligent machines: 3,000 years of robots. Nature, 559(7715), 473-475.

Cave, S., Dihal, K. (2019). Hopes and fears for intelligent machines in fiction and reality. Nat Mach Intell 1, 74–78 https://doi-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/10.1038/s42256-019-0020-9

Chalmers, D.J., (2010) The Singularity: A Philosophical Analysis. Journal of Consciousness Studies. 17( 9-10), 7-65 DOI: https://www-ingentaconnect-com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/contentone/imp/jcs/2010/00000017/f0020009/art00001#

Giuliano, Musa R. (2020) Echoes of myth and magic in the language of Artificial Intelligence. AI & Soc 35, 1009–1024. https://doi-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/10.1007/s00146-020-00966-4

Koch, C., (2015) Will Artificial Intelligence Surpass Our Own? Scientific American Mind. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/will-artificial-intelligence-surpass-our-own/

Kurzweil, R. (2000). The age of spiritual machines: When computers exceed human intelligence. New York: Penguin Books.

Schodt, F. L., (1988) Inside the Robot Kingdom: Japan, Mechatronics, and The Coming Robotopia. New York, Harper & Row 1st ed. — https://search.library.utoronto.ca/details?2076637

Wiener, N. (1964) God and Golem Inc. A Comment on Certain Points where Cybernetics Impinges on Religion. The MIT Press. V. https://doi-org.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/10.7551/mitpress/3316.003.0005